DEFINING THE OBJECT OF INFORMATION QUERIES

SEARCH STRATEGIES

EVALUATING INFORMATION SOURCES

PLAGIARISM, CITATION AND REFERENCING

BIBLIOGRAPHIC MANAGEMENT SOFTWARE

BIBLIOMETRICS

SCIENTIFIC PUBLISHING

DEFINING THE OBJECT OF INFORMATION QUERIES

Structure your research

- Cornell’s 7 steps

You need information on a specific subject (WHAT are you searching for?)

Step 1: Define the topic of your research

Step 2: Find terms and background information in dictionaries or encyclopedias and establish synonyms and hierarchical relations among terms

Step 3: Use catalogues to find book and non-book materials

Step 4: Use digital databases for journal articles

Step 5: Use additional online resources (repositories, digital databases, etc.) to find primary sources and images

Step 6: Evaluate what your results

Step 7: Cite your sources using a standard format

You need information on a specific subject

DEFINE THE TOPIC OF YOUR RESEARCH (WHAT are you searching?)

a) Establish your keywords (words, terms or phrases used to describe the main topic)

b) Find background information and establish synonyms and hierarchical relationships (broader terms, narrower terms, related terms)

c) Brainstorm for concepts and terms and create a concept map

* Concept map is a visual representation of information where several concepts are linked to a main central concept and then connections and cross-links are established between the different concepts in order to discover new relationships between the different areas in your map and this will help you specify the theme of your research

d) Build your search expression using the Boolean operators AND, OR, NOT

RESOURCES (WHERE are you going to look for it?)

For print materials (books, journal titles, journal articles published separately, dissertations & academic materials) USE library catalogues

For non-book materials (CD-ROMs, videos, posters, films, DVDs, audio cassettes, e-books) USE library catalogues

For online materials USE :

- aggregators – tools that combine several databases and other platforms in a single search point

- reference databases

- online library catalogues

- directories – organized lists of contents, organized by subject, publication, and so on, and usually evaluated and noted

- portals – host full-text journals and allow article-level search

- repositories – information systems with scientific and academic content available in open access (OA)

SEARCH STRATEGIES (HOW are you going to do it?)

SUBJECT HEADINGS vs. KEYWORDS

SUBJECT HEADINGS – terms selected or created by a librarian who needs to read through the document (analysis + synthesis) and decide to which subject areas is that document important

- pre-defined controlled vocabulary describing the content of a document (book, journal article, dissertation, film, poster, CD-ROM, letter, etc.) in a library catalogue

- you need to know the exact term, less flexible to search (but you can always Ask the Librarian or use the Helpdesk)

- you look for subject headings in the subject field only

- when too many results, you need to filter them by adding the Boolean operators (AND, NOT, OR) and another subject heading

- results are usually very relevant to the topic

KEYWORDS - the machine recognizes the image of the words as images and no subject analysis is involved

- natural language (a good way to start)

- more flexible to search (multiple combinations possible)

- the database will look for the keywords anywhere in the record (not necessarily connected together)

- too many or too few results (depending if topics are more or less common)

- a lot of irrelevant results (importance of adding filters)

LIBRARY CATALOGUES vs. DIGITAL DATABASES

In a traditional library catalogue (OPAC)

- Use subject headings (controlled vocabulary)

- Define hierarchy or hierarchies your topic could be part of (broader and narrower terms) and if you can’t find a book on your topic, go to the topic immediately above or below in its hierarchy

- Think laterally (related terms)

In a digital database

- Use keywords (natural language)

Types of search for both:

- Simple search - by author, title or subject

- Advanced search - using the Boolean operators AND, OR, NOT (always the more reliable)

Types of information

- Primary sources - authoritative documents relating to a subject

- original documents (diaries, photos, letters, etc.)

- interviews

- videos

- oral statements - maps

- personal blogs

- newspaper articles - Secondary sources - explain or analize primary sources

- encyclopedias

- journal articles

- textbooks

- criticism and analysis

Bottomline…

IT IS IMPORTANT TO KNOW:

- the real topic of your research

- how to build a concept map

- that building your search expression takes time

- how to use the Boolean operators to tailor your research to your needs

- the importance of good research skills and search strategies for accuracy of results

- the language of your resources (how they operate)

- how to use a periodical database (its options and features) and how it works (digital databases are all similar, but they all operate differently

SEARCH STRATEGIES

Online materials

Open Access vs. Subscriptions

EBSCO Discovery Service - discovery service transversal to all 9 NOVA Organic Units.

RUN - NOVA’s institutional repository.

RCAAP - Portuguese Academic Repository at national level.

B-on - a Portuguese academic open access portal for retrieving scientific information accessing simultaneously different research tools.

Subscriptions

Libraries pay an annual fee in order to provide free content to their users.

Open Access databases

|

RCAAP (Repositories of the various Portuguese universities) | https://www.rcaap.pt/ |

|

OpenDOAR (The Directory of Open Access Repositories) | https://v2.sherpa.ac.uk/opendoar/ |

|

DOAJ (Directory of Open Access Journals) | https://doaj.org/ |

|

Doab (Directory of Open Access Books) | https://www.doabooks.org/en/doab |

|

PubMed | https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ |

|

Scielo (Scientific Electronic Library Online) | https://scielo.org/en/ |

|

PLoS (Public Library of Science) | https://plos.org/ |

|

BenthamOpen | https://benthamopen.com/ |

EVALUATING INFORMATION SOURCES

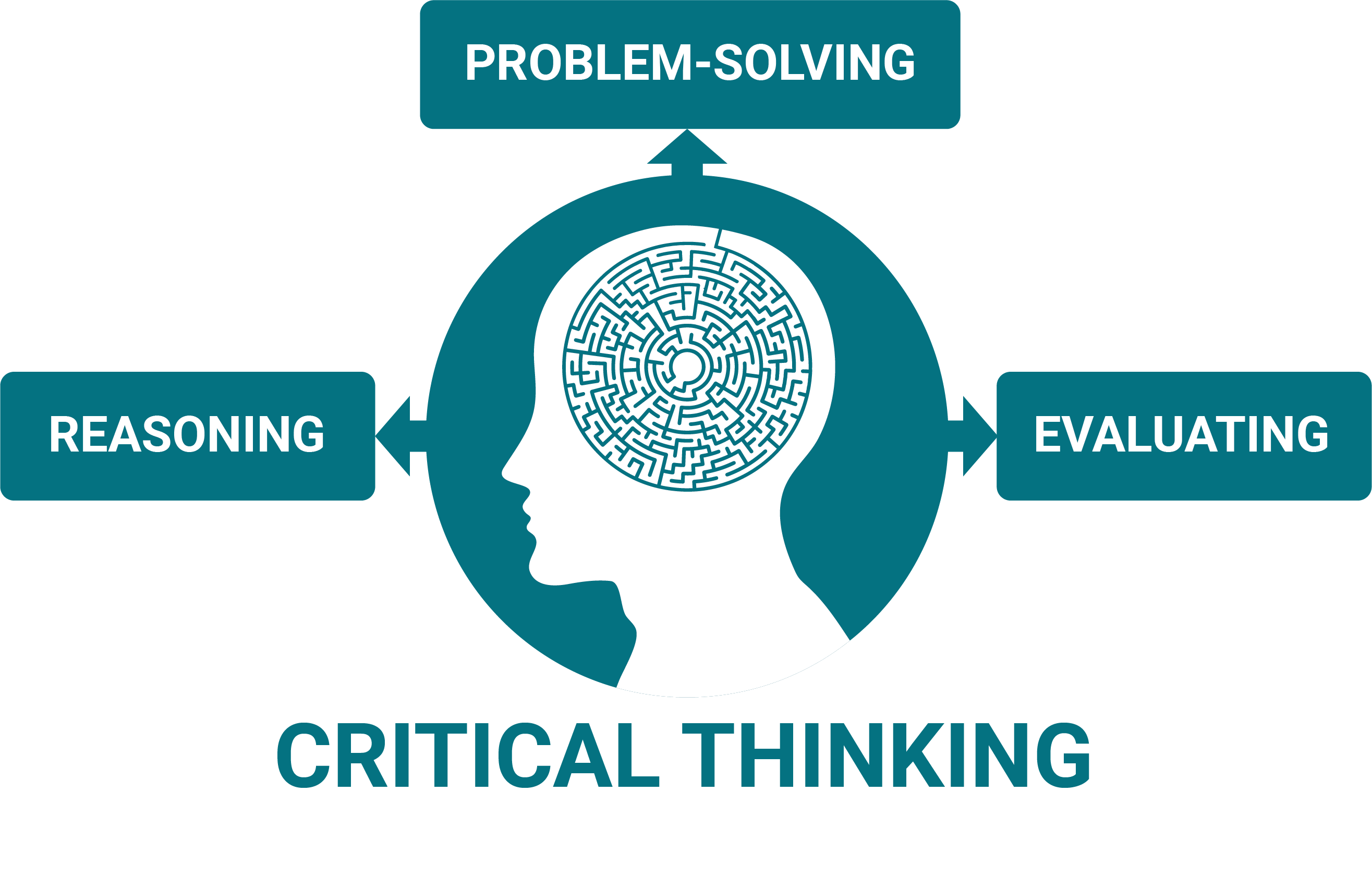

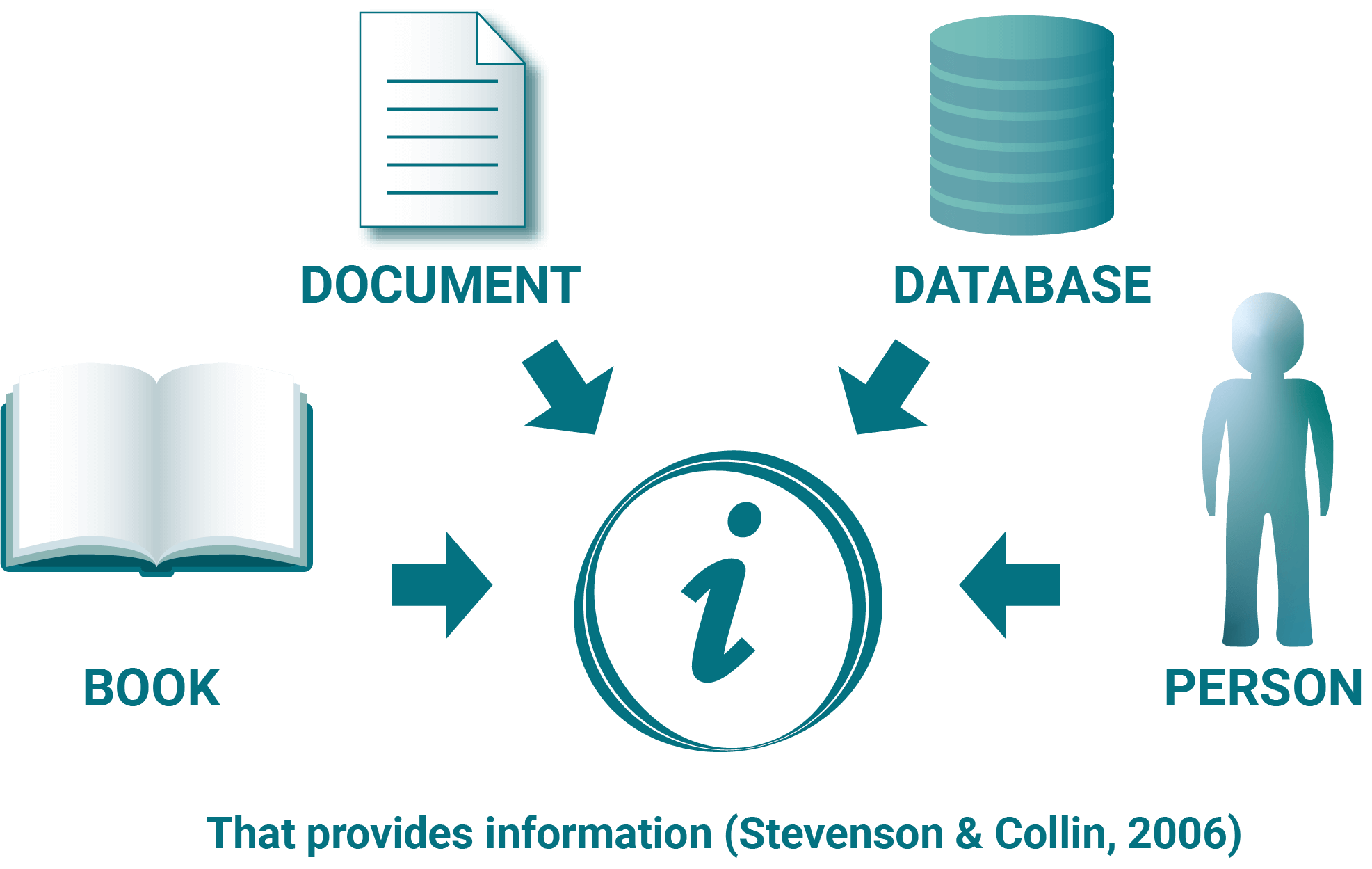

Evaluating information sources requires critical thinking, identifying the type of information you are looking for, and understanding + and – of various types of sources.

The nature of your topic may determine which format is best for you. A combination is the best way to find information.

Criteria for evaluating information sources

Although we can say that every “traditional” resource has been evaluated in one way or another, we must always apply classical and generic criteria for the evaluation of information sources.

You should apply evaluation criteria to any information you find on the Internet.

YOU NEED TO CITE INFORMATION FROM THE INTERNET AS YOU WOULD CITE ANY OTHER INFORMATION.

Problems in applying “classical” quality evaluation criteria to web information sources

CURRENCY – the timeliness of information.

The date is not always included. When it is, it can mean different things:

- date of writing

- date of editing

- date of last review

RELEVANCE – the importance of the information for your needs

Relevance considers the importance of the information for your research needs. A relevant information source answers your research question. To determine relevance, the purpose and bias must be understood. In fact, all aspects of evaluation must be taken into consideration to determine relevance.

AUTHORITY – the author of the information.

The authority is often shared and difficult to determine; when is it indicated there are no elements about what qualifications the author owns.

ACCURACY – the reliability, truthfulness & correctness of the content.

Information is shared without being checked and verified in other sources.

PURPOSE – the reason the information exists.

The purpose of the source and its targeted audience is difficult to determine because of poor structure, information overflow, too many links, etc. It is not clear if the source is published, sponsored or endorsed by a special interest group or not. There is no clear indication of the authors’ perspective on the issue presented.

BOTTOMLINE

Not all information is useful, accurate, up-to-date, unbiased and appropriate for your research.

Using an index or database to find information gives us reassurance that it was produced by a professional or scholarly organization that selects them on the basis of their quality.

When we are using the World Wide Web, none of this applies.

THOSE FILTERS ARE OUR RESPONSIBILITY.

PLAGIARISM, CITATION AND REFERENCING

Strategies to avoid plagiarism

- Know how to avoid plagiarism (understand the concept, knowing how to recognize different types of plagiarism, know why it happens, realize the consequences of plagiarizing).

- Understand which information we can use and how.

- Know how to integrate bibliographic sources in an academic work, recognize norms and bibliographic styles, identify the syntax of a bibliographic reference.

- Know how to use a bibliographic management software.

- Know how to use a plagiarism detection software.

What is plagiarism?

- Use someone else's idea without referring to the source from which that information was taken (text, photo, graphic, image, audiovisual work, etc.)

- Whether you are an author who has published a work or not, another student, a website whose authorship is not clearly identified, or anyone else.

- Not referring to a source is equivalent to “stealing” someone else's work.

- It is considered unacceptable in all academic situations, whether committed intentionally or unintentionally.

If we do not cite sources, we are committing plagiarism and infringing copyright that includes:

- Moral rights– the right of being recognized as the author.

- Property rights– the right to produce, publish and sell the work.

Fom more information, please check the Code of Authors' Rights / Copyright and related rights available at your country.

Within the right to publish, the author may use a creative commons license to make his work available on the internet.

For more information about creative commons licences, please visit https://creativecommons.org/ or go to the section on creative commons in this Survival Kit.

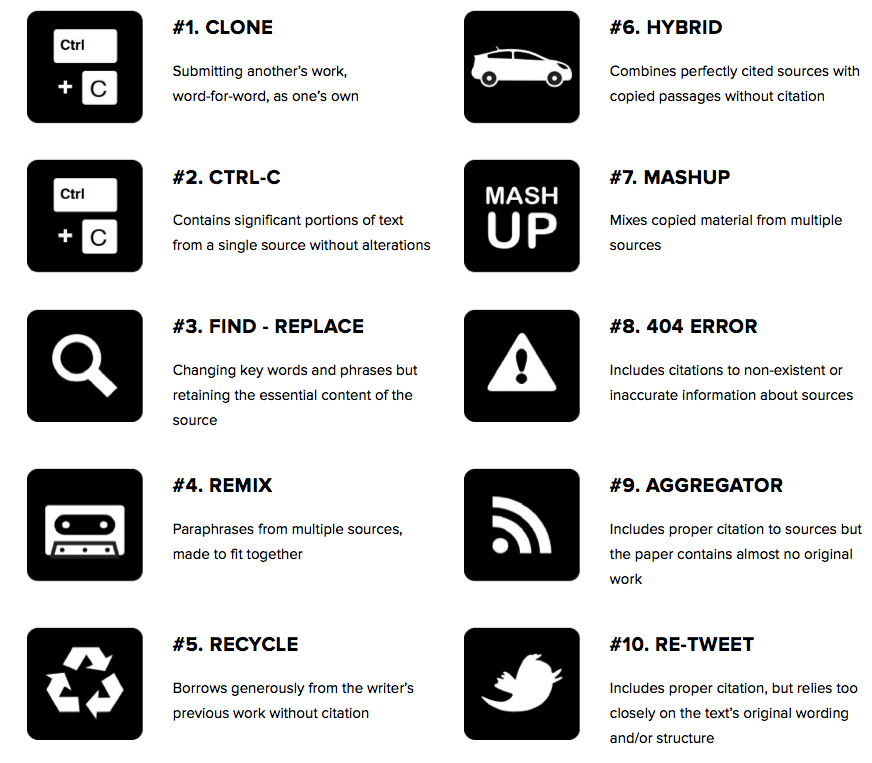

Different forms of plagiarism

Source: https://whittier.libguides.com/c.php?g=346305&p=2334848

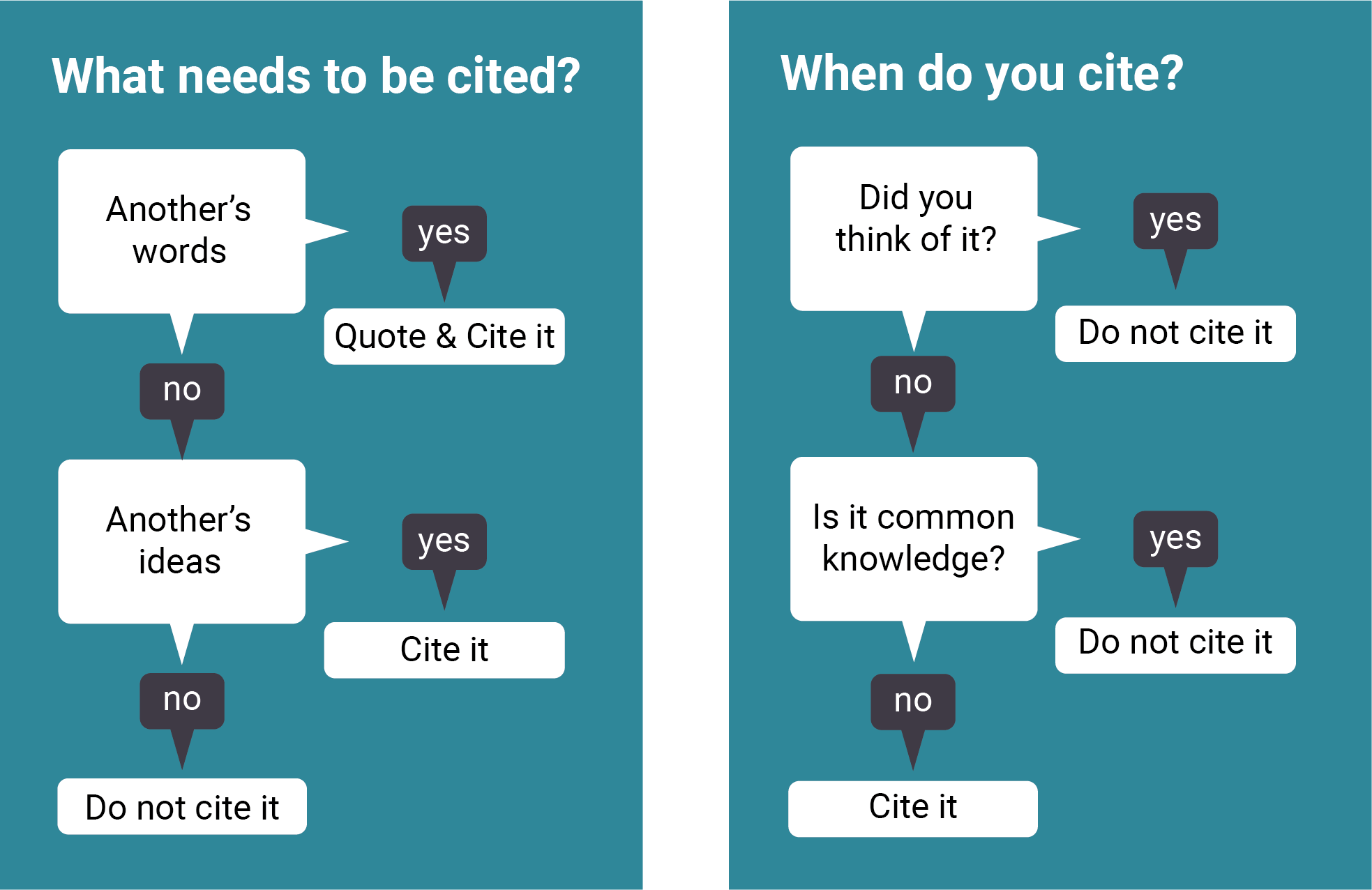

When/what do we need to quote?

Source: Harris, Robert A. The Plagiarism Handbook: Strategies for Preventing, Detecting, and Dealing with Plagiarism. Los Angeles: Pyrczak Publishing, 2001

Anti-plagiarism software

- Turn it in - compares a student submission against an archive of Internet documents, previously submitted.

- It creates an 'Originality Report' which can be viewed by both lecturers and students, which identifies where the text within a student submission has matched another source.

- It’s important to note that Turnitin does not detect plagiarism. It will only match the text within a student's assignment to text located elsewhere (e.g. found on the Internet, within journals or on databases).

- Correct interpretation of these results by both lecturers and students is essential for the successful use of Turnitin.

For more information please visit https://services.anu.edu.au/information-technology/software-systems/turnitin/turnitin-frequently-asked-questions-faqs-for-0#_01.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC MANAGEMENT SOFTWARE

They are software programs that allow you to collect, store, organize and manage documents of different types.

These software allow you to import bibliographic metadata - as well as PDF files when available - from databases, library catalogs and other online platforms, as well as PDFs previously stored on your computer.

They are like small, fully searchable databases.

Among other features, these tools allow you to insert and manage citations and bibliographic references directly in word processors.

They are compatible and it is possible to import/export reference files in BibTex, RIS and other formats, between software.

There are several bibliographic management software, many of which are available for free.

Generally speaking they all perform the same functions.

- Import documents and their metadata from databases, library catalogs and other online platforms.

- Save pdf's of documents.

- Import pdf’s from folders saved on our personal computers.

- Integration with word processors.

Amongst the software available for free, we highlight Mendeley, Zotero, JabRef (mostly used by those who write in LaTex), Papers for those who use Macintosh computers and EndNote (online), a Clarivate Analytics/Web of Science product, free for the community of higher education in Portugal.

BIBLIOMETRICS

- What are the best journals in my field?

- Which journal should I publish in?

- Who is citing my articles?

- How many times have I been cited?

- How do I know this article is important?

Bibliographic databases that are used by University Rankings or by the Organization the researcher works at such as Web of Science (Clarivate Analytics) or Scopus (Elsevier).

In your best interest you should be prepared to understand what you are asked in grant proposal forms but also to understand the importance of these numbers in budget cuts.

In social sciences this might not be as important at the individual level but as member of a university all areas are considered.

Quantitative indicators are used for:

- Research assessment

- Job applications

- Grant proposals (funding)

- Department/Institutional evaluation

Be aware of the limitations of quantitative assessment and use them in your advantage.

- Publish in indexed journals with high impact factor.

- Archive your publications in your Institution’s repository.

- Publish open access when possible.

- Maintain an online presence for your work with no social/personal information.

- Create and maintain your researcher profile such as ORCiD, Ciência Vitae or Google Scholar.

SCIENTIFIC PUBLISHING

- Identify the most important journals in your field of study.

- Follow all of the author guidelines: format, citations, references, length, submission policies.

- Avoid breaches in academic integrity: manipulation of results, images, etc., plagiarism, multiple submissions, failure to acknowledge prior research and researchers, and inappropriate identification of all co-authors (ghost and gift authorship).

- Responding to the review, read comments objectively and reconcile them to your manuscript’s purpose and intent; update bibliography if necessary.

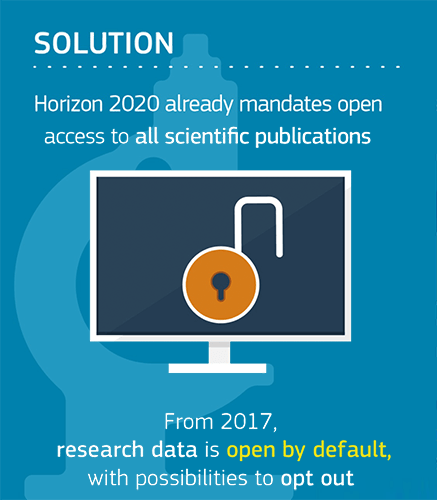

- If you benefit from public financing (including scholarships) or the EC (among other funders), you need to make your publications open access

- Any type of publication

- Author decides to follow the gold (immediate OA) or green (archive a copy in a repository) road

- Either way, it’s mandatory to deposit a copy in a repository from RCAAP directory (e.g. https://run.unl.pt/)

- Embargo periods vary according to publication type

For further information, please visit:

https://www.fct.pt/documentos/PoliticaAcessoAberto_Publicacoes.pdf

- Use white lists of OA journals such as the Directory of Open Access Journals

- OA journals may not charge (diamond journals) or have lower APCs

- Hybrid journals’ APCs are higher than full-OA journals (and most funders will not reimburse them)

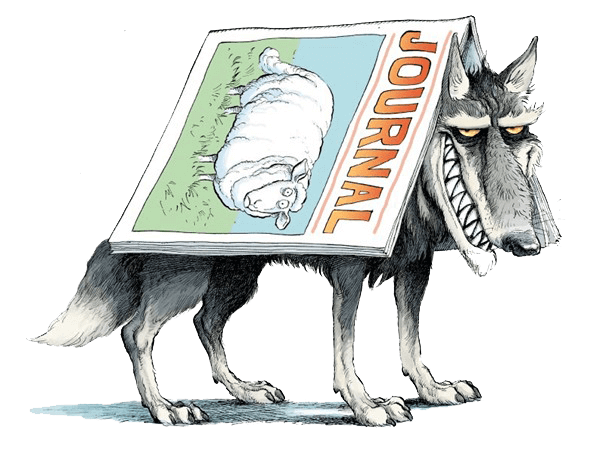

- Beware of predatory journals

- Use Think.Check.Submit to verify if the publisher is trustworthy

- Check journal self-archiving policy on the publisher’s website

- SHERPA RoMEO (self-archiving & copyright policies of international journals)

- DULCINEA (Spanish journals)

- Mirabel (French journals)

- Diadorim (Brazilian journals)

If you benefit from public financing (including scholarships) or the EC (among other funders), you need to publish your research data

- In a certified repository

- Data underlying publications and other data

- As open as possible, as closed as necessary: exceptions to data sharing need justification

- Also, actively manage your research data

- Data should be FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable)

- Use Persistent Identifyers (PIDs)

- Associate licenses: CC-0 to metadata and CC-BY to data

- Data management plan mandatory

- Compliance will be monitored

For further information, please visit https://ec.europa.eu/info/funding-tenders/opportunities/docs/2021-2027/common/agr-contr/general-mga_horizon-euratom_en.pdf

The incorrect use of bibliometric indicators for the assessment of individuals led to a movement requesting the reform of the research assessment system.

DORA San Francisco Declaration (2012) "Do not use journal-based metrics, such as Journal Impact Factors, as a surrogate measure of the quality of individual research articles, to assess an individual scientist’s contributions, or in hiring, promotion, or funding decisions".

Leiden manifesto for research metrics (2015)

Evaluation of research careers fully acknowledging open science practices (2017)

Towards a reform of the research assessment system (2021)

Deutsch

Deutsch